How we raised $3M for an open source project

Jun 04, 2020

On this page

- Why raise money at all

- Venture Capital (VC)

- Bootstrapping

- Donations

- Converting an Open Source project into a business

- Product<>Community versus Product<>Market fit

- Making money

- How long it took

- VCs are nice

- The impact of coronavirus

- "You're too early"

- The 'fundraising battlestation'

- Hardware

- Software

- Investor CRM

- Markdown notes

- Captable management

- Legal doc management

- The process

- Get meetings

- Plan the meeting

- Do the meeting

- Follow up

- Raising in the US when you live in a different country

- The paperwork you'll need

- Getting the first cheque

- Getting the right investors

Open source projects have long battled with how to finance themselves. PostHog is lucky to have significant funding and wanted to share what we did to help other cool projects take off.

For those who've not met us before, PostHog provide open source product analytics. We went through the Y Combinator W20 batch, which took place from January to March 2020. We have raised $3.025M in funding really quickly, and wanted to share what we did. We may well not be a typical company, but we would hope this gives some lessons learned regardless.

Why raise money at all

Before you decide if you want to raise money, it's important to know what you are trying to achieve and to optimize for that.

Many projects don't ever want to become businesses - if it's just a hobby and you don't want to speed up, you should just keep doing that :)

We felt building a company around the project at the same time would let us build something really ambitious, so we did that.

So, what are your options for funding?

Venture Capital (VC)

VC means you have way, way more cash to fuel your project's growth, if you spend the money wisely. That's pretty much the advantage. You will obviously have to build a company around the project so you have a way of making money at least in the long run.

Depending very heavily on the firm, you may get a lot of support with meeting early customers to generate revenue later on, hiring, free VC swag and your strategy. You can always ask the partners and founders from their portfolio to get a sense of what working with them is like.

We felt personally the challenge of managing accelerated growth would be a lot more stimulating, and that has certainly been the case so far!

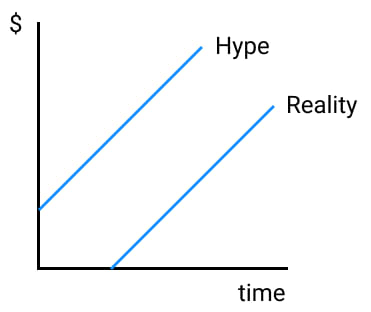

VC hype begets a bigger team, begets results (hopefully), begets hype:

Especially early on, VC is buying into your potential value. This makes sense - if the company that forms around your project has a 1% chance of being worth $1Bn or more, it is rational for people to take that bet if the price is right. Open source companies really can make it big - it's a post for another time, but we believe that open source will eat SaaS's lunch in many product categories.

The way to pitch open source to VCs is that it is easier to get into production, and there is less of a sense of vendor lock in, which puts off many developers from trying out a new SaaS product. SaaS may be "less work" to manage, but there's probably no reason you can't also provide your own product, hosted. The end result is that your open source repo could get used at huge companies. They probably have needs your free product can't deliver (uptime, better features, support), which you can make money from meeting (through providing services, hosting or premium features), to invest back into the project.

The downside of this VC route is that you risk hype<>reality disonance!

If you can't achieve results with the money you raised, whilst increasing your burn rate, you are at the mercy of those funding you if you will survive. Not cool, but you took this route!

You also have investors, who have given you lots of money. Don't fall in love with them - you must prioritize your own team and their performance, then users then customers, in that order. Do that, with a good strategy, and your investors will take care of themselves.

Oh, and you can't pay yourself a huge dividend if you succeed as a way of taking money out of the company, although it might become possible to sell some shares later if you're rocketing (perhaps to help you keep taking risk), and in the short run, you can now probably afford to pay yourself something - hoorah for being able to work on open source full time! Going for VC means you are committing to an exit or a failure - you can't really change your mind later that you want to take things more steadily.

Turning your project into a VC backed company means you will have to spend a lot more time dealing with people.

Investors, a larger team, probably more customers, and probably a larger community. Depending on your personality, this might be a good or a bad thing. If you built the project in the first place for the fun of building, you should think hard about this. If you find the concept of treating the company itself as your product not just the repo, then you'll enjoy it!

PostHog chose the VC route. We wanted to build a company as a way of being really ambitious with what we can do with product analytics. We want to help every developer have a better understanding of the impact of their work.

Personally, when we're 80, we think we want to have taken a couple of big swings with our careers even if we don't own the whole pie. On the product side, we can build something open source that will outlast us if we get it wrong, and regardless of the outcome, the skills and lessons it will give us will help us in our future lives.

Bootstrapping

By this we mean getting real customers to pay you money, to reinvest into the project's development, and fuelling (or not) your own growth at whatever pace you see fit.

Basecamp have a great philosophy on this.

You get complete control this way. That might make it easier to do the "right thing", or to be more creative in what you build since you won't have to be disrupting or creating a multi billion dollar market as a constraint. However, the financial pressure of payroll in the early days might make it tough to optimize for long run decisions. You need to feed yourself somehow!

Humans get tired and hungry. Not giving up is what we saw as the major challenge of this way of working.

We felt this was a similarly high level of risk to inflating your burn rate above your revenue that comes from VC, especially with open source where you'll have to manage to build a free product first, then a paid version (unless you go down the hosted = paid route).

Donations

If it's a side project and you have no need to support yourself, you can use Patreon or similar to ask for donations from your fans.

The fundamental problem with this is there's not a strong incentive for companies to donate money, and even if they do, the amount is typically a fraction of what they would spend on paid software. That means it will be very hard to support yourself to go fulltime, let alone to grow a team to go even further with the project.

However, this could be a cool way to start before doing bootstrapping or VC in the future. There are good reasons for keeping some things as a side project or hobby - you can be more creative, and just build things for the fun of it.

From this point on, we're going to explain how we raised venture capital in this post.

Converting an Open Source project into a business

This is a controversial topic as it creates all kinds of incentives, but for at least our project, it fundamentally made the entire thing possible in the first place. We just wouldn't have gone ahead if we were working on it at weekends or in our spare time.

Product<>Community versus Product<>Market fit

We'd advocate that the best way to build a really ambitious, fundable open source project is to get something to ubiquity before anything else.

In SaaS, there is a lot of advice to charge money even before you have a product. It is almost becoming a standard approach. You somehow have to jump to product<>market fit in one leap to achieve this - you need to have a product concept that is so strong people will pay upfront. That means getting to product<>market fit is incredibly hard since there are too many variables to know how to solve the puzzle except through trial and error. However, when you get there, making money is easy.

Open source creates a different route. You need to (i) build something useful THEN (ii) work out how to make money. You'll get much, much more feedback from open source - it's an approach that is more developer-friendly and thus will tend to get you a lot more growth and adoption if you are getting close to something useful. That makes it a lot easier to build something useful for a community.

However, making money is harder. You will need to do that to sustain and grow the project. You need to have faith that once you've built something useful, you'll be able to work this out. PostHog, even at our current scale, get one or two paid enquiries per week inbound. We speak to these people to try to understand what they'd need and if they'd then pay for it. Most run off - we're still learning! That said, we still ourselves have work to do on making our own community and free product stronger before worrying about revenue.

The good news is that inbound interest is much, much easier to close, and you don't have to waste time sending hundreds of cold emails to generate it - you can focus on the free product.

This can definitely go wrong - you could run out of cash before you reach product<>market fit. You might accidentally build a free product that has no viable commercial route. You may find that the market you are building for is too small for VCs to be able to invest into it.

When we raised money, VCs asked about the commercial side, but the ones that invested generally just have the belief that product<>market fit is easy once you get product{<>}community fit. We were upfront about our paid version - we don't know how it would work yet, but we have a plan for how we'd approach it.

Making money

You'll need some way of making money, at some point. That'll come after product<>community fit.

There are three popular ways of doing this, either:

- Services

- Hosted

- Open core

- or even some combo of the above (but don't make it too complex)

There are probably other ways (Ads? Although yuck) that we haven't thought of.

A services approach is pretty simple although if it's the only plan in the long run, it'll make generating a high valuation tough, so raising money will be more painful. That's because services are low margin - selling time rather than a scalable product doesn't improve your returns as you get bigger.

By hosted, we mean charging customers for the hosted version of the open source product. The risk is that a cloud provider decides to compete with your hosted version. There is licensing to prevent this, although it will make you technically "not" open source, which may harm adoption and the fit with the community. Lots of developers can use MIT license software in big enterprises, but they can't use licenses that prevent commercial use without some form of approval from their company (if they work at a big company).

The upside of charging for hosted use is that you don't have to build anything beyond your basic product, and that means all your attention that goes into your free version will help the paid version's growth too.

Open core is the model of choice for PostHog in the long run. We made a hosted version in the short run just to see if we could passively make some money to help control our burn rate (although a payment flow is on the todo list still…!), and it turned out around 60% of our users go for that route to try it out. We think that's a great sign.

For open core, you first build a Community Edition open source product and focus on being really helpful to everyone who is willing to try it out or contribute.

Do a really good job of that and you'll get random emails from folks at bigger companies who need more support or extra features. You can then build a "source available" version that you charge monthly for, for those people with premium functionality. The disadvantage is you have to build premium features that you can't put into the open source version - and it's important to be really upfront with the community about what is free versus paid… since that may put some developers off from doing pull requests, for example.

How long it took

- August 2019: Tim and I quit our jobs.

- January 4th 2020: We started the YC W20 batch, and that meant receiving our first $150K investment from YC. We worked on a different idea to start with but soon pivoted.

- January 23rd 2020: We wrote the first line of code for PostHog

- February 14th: We did a mini launch for a few YC companies to get early feedback

- February 21st: PostHog launched on Hacker News

- March 6th: Day 1 of fundraising and first cheque ($10K!)

- March 12th: Left San Francisco due to covid and started working fully remote from the UK. Everything seemed to slow down at this point for 3 weeks. Our bank balance was $205K this day.

- March 16th: Demo day.

- March 31st: Balance: $530K.

- April 24th: Balance: $719K

- April 26th: Seed round completed at $3.025M - when you start closing bigger cheques, it wraps up very, very fast.

There was one thing we never expected to happen - we ended up with offers for "too much" money and could have raised $5.5M. We're trying not to humblebrag, but it is kind of weird. We already sold quite a lot of the company and didn't want to sell more - the money raised already was enough we felt to get to a really good series A.

We had to shift from selling ourselves to investors, to having to let investors down. This made us feel pretty guilty after all the meetings and relationships that we had built, but it was a great problem to have, and we tried to be as upfront as possible through the process.

VCs are nice

It may have been luck, but we didn't have a single negative interaction the entire way through this process. People wanted to understand what we're working on, they were encouraging and very helpful - even when they said no in many cases. A lot of the meetings were very intense and direct, but those were the most helpful ones of all. If you can handle QA, you can handle VC!

The impact of coronavirus

Coronavirus' impact made fundraising harder. We had started raising as the virus was spreading in China, but before it had affected the US significantly.

During the raise, that changed and lockdown came into place. Suddenly, we were asking complete strangers, in a different country, for millions of dollars to fund our pre-revenue business, over the internet. The first three weeks after lockdown, the process came to a halt - no one seemed to move forward, and a couple of late stage firms with us pulled out for this reason.

Tim and I had been living together in San Francisco for the YC batch. When we saw the ban on flights from Europe to the US, we both decided to go back to the UK so we wouldn't end up getting stuck and overstaying our visas. We were both also worried about being stuck away from our families for a very long time. It was nice to be with family again, but the compromise was working West Coast US hours whilst living in a London timezone. It did at times feel like the fundraising cycle may never end - a bit like wrestling a bear, you're done when the bear is done. We promised ourselves that we would not use the virus as a reason to not raise not matter how tempting it was to stop and to come back later with more usage - it risked killing our momentum.

However, after a couple more weeks, it felt like the VCs had become used to this process - they do dozens of meetings every week, so it didn't take long to adapt to "over the internet" fundraising becoming the new normal. We stopped discussing how lockdown was affecting each other on calls, and started getting more people closer to investing in PostHog.

"You're too early"

It sounds obvious, but many of the most successful open source companies start off with a really popular open source project. The implication is that you're going to have to build something that gets popular first, then monetize later, in most cases.

From a fundraising perspective, this means you can either be raising (i) off the back of lots of revenue, which seems unlikely or (ii) from a ton of growth of the project.

It means you'll probably need more money than a SaaS company to get off the ground - you'll need to find product-community fit first. You'll also need to make sure the potential investors you speak with agree on this point. We took this stance more and more firmly through our pitches and realized it polarized investors - which is a good thing. At first we were like "we'll sort of work on making money and getting lots of users", which just isn't credible.

Polarize people (without being rude of course!), then you'll find those that can share your passion.

The 'fundraising battlestation'

Hardware

If I were to do this again I'd probably put more effort into the setup given how many video calls I ended up making.

"You want to at least look like you have your **** together" - a YC Partner describing how to do video calls with investors. Not sure I quite nailed that.

The physical notepad helps during calls - sometimes people ask "compounded" questions, so it can help to jot down areas you'll want to come back to. Other times, you may find yourself "pushing back" a topic to later in the call to keep the flow more natural, so you can make sure you remember to loop back. It somehow feels less rude to be physically writing than typing - it doesn't create the illusion that you could be browsing social media whilst talking.

The lamp is there to help out with lighting a little, and the laptop stand is to prevent an unflattering angle on the video.

The snack bowl is so I don't eat an entire bag of chips in one sitting.

Software

Investor CRM

I created a Google Sheet to track statuses of each potential investor. This stored:

- firm name

- individual partner / associate

- potential cheque size

- interest /10

- next step

- type

- added to Pulley?

- SAFE status (if applicable)? (sent / signed / money received)

You could use AirTable or a real CRM, but PostHog are by default opposed to introducing new software.

Markdown notes

This was handy to store more context than is possible in as spreadsheet.

The format was a single long document, with more detailed notes that I stored as a private repo. I just had 5-10 bullet points about each person I was meeting and their firm, that I would generate during the planning process.

Captable management

We used Pulley for this. Captable.io is a well known alternative.

This software helps you model out how much of the company you are selling. You can experiment with different scenarios and their impact at series A stage.

We tried doing this on spreadsheets but it quickly became apparent we couldn't quite get the maths right. We found cap tables weirdly hard to do. That's probably just us.

Legal doc management

We used Clerky. It generates all the legal paperwork you need for raising money, and many other things. I'm a big fan.

The process

Fundraising involves dozens or hundreds of meetings. Seriously.

You will find yourself brought to your administrative knees if you do not run an organized process.

Get meetings

They came from two places. Either (i) I had to get introduced to someone or (ii) I had responded to inbound interest.

We only sent 1 cold message and got asked for a bunch of detail then ignored. It turns out, this isn't how VC really works. That said, I'm sure there are exceptions and perhaps we had a biased view because our network in San Francisco was strong from having been through YC out there.

How did we get introductions? We always made an effort to be buddies with other founders - whether through helping people out, becoming friends with users or politely asking for advice from other founders that we look up to. If people believe in what you're working on, they will be happy to introduce you to others. The better your idea, the closer your relationships and the more traction you have, the more success you'll have here.

Investors must miss out on so many deals because of this, yet it's a weird form of social proof that I guess must work even if it means missing false positives. I imagine this is quite socially harmful - if you're network is weaker and further from the most decisive VCs, you will have a harder time raising money for your company.

It strikes me that YC's application form process doesn't work that way at all - we did no hustle to get in.

On the flipside, as it turned out, weirdly, not a single cold outreach email that we received ourselves from investors wanting to meet us, turned into an investment. It turned out that investors who made the effort to reach out to us through another investor did end up making an offer.

Make yourself easy to contact - my LinkedIn profile views doubled during the fundraise. Update your social media and put contact details onto your website or readme. Include your phone number in footers of your emails. Create a crunchbase profile, update your LinkedIn and Twitter. We were getting at least 1 inbound request from a VC per week almost immediately on creating a website. During YC, that climbed to nearly 1 per day. These converted poorly but we did get partner meetings from many of them, which gave us valuable experience.

Plan the meeting

You should find out a reasonable amount of information about the person you are meeting. Beyond just looking at the portfolio for the firm, look for a couple of blog posts, and try to work out if the investor is on the board of any companies. That'll help the meeting run as a discussion and, bonus, will help you realize if there is a conflict (if an investor has competed in a direct competitor, you probably shouldn't talk to them let alone partner with them).

The portfolio itself can also be useful. Are there any similar companies you could compare yourself to?

Do the meeting

It should feel like you are driving - you made it happen, after all.

Start by introducing yourself, give the company one-liner, and have the investor do the same. Try to get a good sense of who the investor really is - they could be working with you for a very long time.

There's basic information that you should find out every time, if you can't work it out online beforehand. For example, do they follow on (you'll need that info later), what sort of cheque size they prefer to work with, and if they are a firm rather than an angel, do they have an ownership requirement, and are they comfortable leading a round.

Later in the discussion, you should make sure to find out how they make decisions - angels may decide on the call, seed firms will often decide after another 2-3 calls with a couple of partners involved, multi stage firms may require a full partner meeting. Just get a sense of how long it normally takes too - some can make a decision in day, others take weeks or months.

You'll probably get asked where you're at in the process. This is where it's helpful if you've a couple of angels early on - they will help you set a price and will demonstrate some momentum at least. Angels are a lot friendlier and many are willing to back companies that are just starting to raise. However, you should, even at that stage, have a least a point of view on how much money

How do you value your company? There are plenty of good guides out there. It's key to note that you set the price - you'll get feedback pretty quickly if it's too high. If you trust angels that you are speaking to, ask them what they think.

We used the YC seed deck. Some people get really into the quality and design. Ours was black and white with a logo copy pasted onto the front. Maybe if we were in B2C this would have been more important.

Subtle sidenote advertisement: we actually do really want to drive design more heavily into the core of how we work. Please email me if you're a UX person - please send your portfolio if you have one.

We didn't present the slides in the meeting, but we'd send them afterwards - we used this approach to structure how we talked about ourselves - there were a (tiny) handful of main points we wanted to make.

In the meeting itself, ask the investor's opinions - it is a brilliant way to get advice on strategy and your company from people that can pattern match against hundreds of others. Not all investors will give the same advice, particularly for open source where the business models are a little nascent. Some will tell you to focus on revenue, others will push towards adoption, others will do something between the two.

You can do this positively to work out what to focus on "what would you want us to achieve with this round", or to help improve your pitch "what do you see as our biggest risk / what would stop you from investing in us".

Follow up

This usually involves sending slides and a demo video (which we thought was a cool way to show the product off), then follow up booking another meeting. We weren't perfect, but it's clearly obvious that if you can respond immediately after the meeting, you'll accelerate your own fundraising process and you've got the attention of the investor at that point rather than giving them time to get onto the next call.

Once that's done, take a moment to think if anything could have been better for next time. If you get rejected, we found investors were very helpful and nice with giving feedback - just bear in mind the reason for rejection may not be the real reason. Did they just walk out of a bad meeting with their LPs, or did they get burned by a similar company once before? There's an incentive for them not to tell you these things.

Do not underestimate how much pipeline you need to build. There is a lot of legwork. My investor spreadsheet ended up with 157 rows.

That number doesn't reflect that we often had 2 - 5 meetings with the same person. I would estimate I did about 200 calls, each lasting about 45 minutes, in ~6 weeks, on top of all the booking meetings in. We probably had 30 rejections, usually due to us being "too early", often coming from investors who hadn't invested in open source companies before. At first, these felt disheartening, but after a while it became clear some people love what we're working on, and others don't, so we stopped caring! We ended up with the possibility of raising $5.5M and got really oversubscribed with investors fighting to get in, but it didn't feel like that would happen at first.

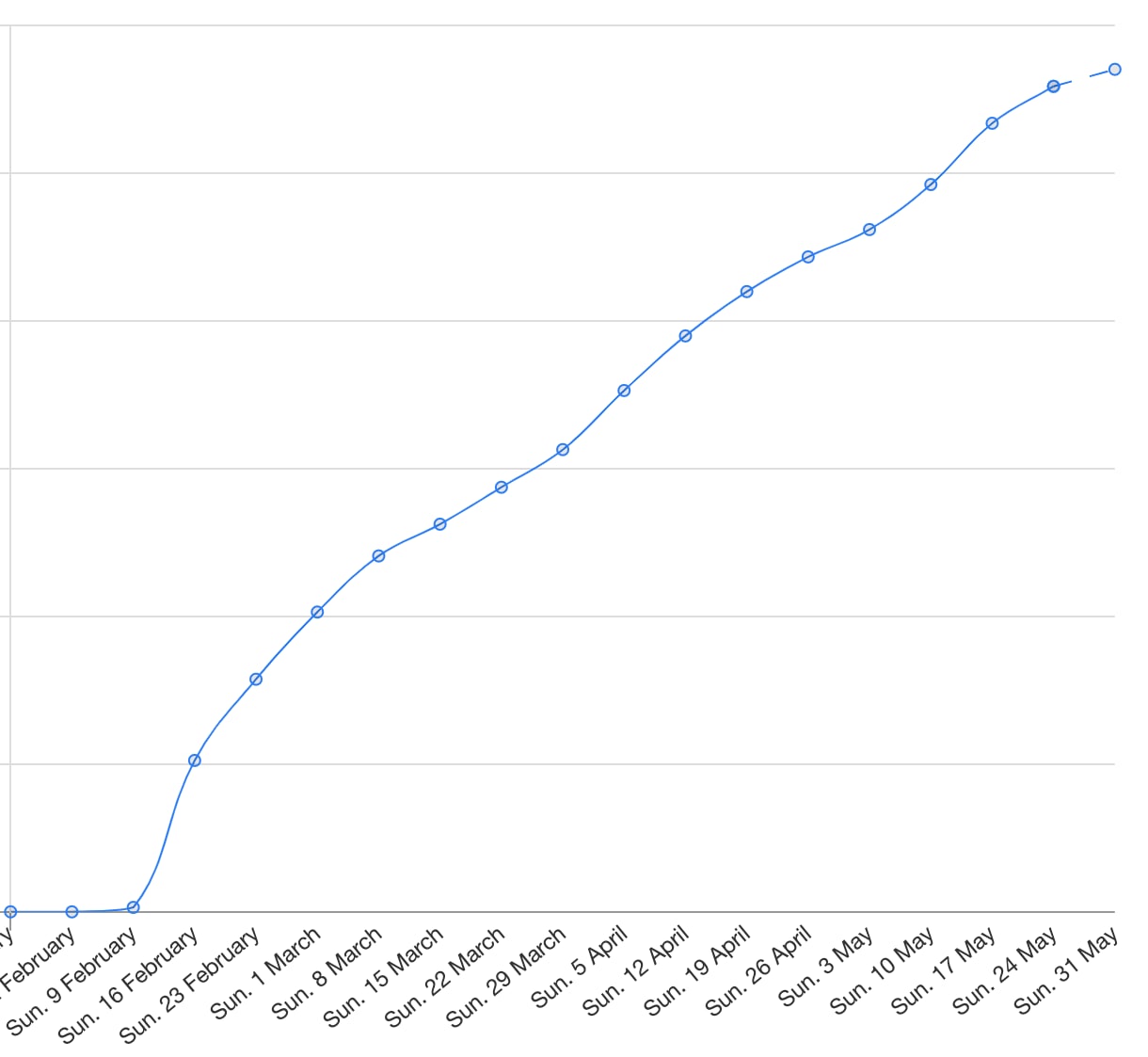

It was very important that we kept the product getting better and our usage growing during this time. I focused exclusively on the fundraising process, and Tim focused exclusively on building the product with our kick ass team and helping out the community. It would have been much harder if we were solo founders. Some investors during the process of talking to us saw our user number double. ie our user numbers did this:

Eventually, after the first 4 weeks, we started realizing in the data that there was a clear trend for who seemed the most engaged: general investors < investors with many developer tools companies in their portfolio < investors with a significant open source portfolio. The close rates of the last category was astronomically higher.

You will also probably need some users to be references, often repeatedly. We had four or five who did this for us and we will forever be grateful / send bottles of wine in the post afterwards.

If you ever speak to a happy user, or you get nice feedback on Twitter, ask them very nicely - most people find talking to VCs a fun opportunity. We tried to connect users we felt would be able to explain our software to a less technical audience to make sure these went well.

If you close an investor, it is a really good idea to make sure you then get introductions to whomever else they'd think your company could be a good fit for. We got the majority of our investment this way. You are not supposed to do this from investors that rejected you though (although that happened without us asking and also led to a lot of investment once or twice, but I would always decline offers to introduce us to others if an investor said no).

Raising in the US when you live in a different country

PostHog is proud to be remote first. We think that's a big advantage for open source companies. It means your users and community get to know you properly so it's easier to make friends with actual people who dig your stuff. We aren't a faceless corporation in an office somewhere. That's why I write posts like this.

The reason we chose to raise in the US and to create a US company, even as UK residents, was that we believed it would give us the best swing for the fences. Moving to San Francisco for the YC batch meant we'd be amongst the highest concentration of founders of companies both big and small in order to learn as quickly as possible. We won't move to San Francisco permanently for family reasons, but we will travel there frequently for this purpose.

It became clear, the same is true - at least for us - on the VC side. Not all, but the majority of UK investors we spoke with, felt the valuation was too high. I'd hazard a guess that we'd have $5M post money valuation in the UK (which would have meant we'd have needed to raise a lot less), whereas we ended up raising at $15M post. We can see why investors can be more risk averse - they can get into more companies if each company has a lower price. However, from the company's perspective, more money means you have more resource to hit a homerun, which is what has to happen for the majority of VCs to be successful. There is some interesting albeit old data on how raising more money increases your chance of success later (although perhaps this is correlation not causation), but only up to a certain point.

The paperwork you'll need

If you're raising money in the US, we'd recommend you have a US parent company. You can "flip" your existing company to have a US parent - this cost us $10k, which was a frustrating expense, but a necessary one that was far outweighed in financial terms by raising in a more competitive market. If you don't have a company formed for your project already, I'd just set up directly as a US company, and I'd definitely pay a US attorney to do that for you. You will have to have some money to do that, and it'll mean you need to get an accountant to do taxes. Tim and I saved up before we started and used our own money for this.

Once the company was incorporated (which we had to do to get YC's $150k initial investment in regardless so we were extra incentivized), we (/ our lawyer) created an employee options pool then raised our entire round on SAFEs. SAFEs allow investors to invest without you having to create a priced round which costs usually a minimum of $25K or so, unless you use the Series Seed paperwork. They are quick to sign, with no legal work needed.

We set a cap with investors. We started off with a $12M post money cap, meaning that the first $200K or so that we raised guaranteed those investors that if our eventual priced round went over $12M valuation, they'd get a lower price as a reward for investing early thus getting a higher fraction of the company for the same money. After starting with angel investors on this basis, we decided fundraising was going well so we increased the cap to $15M. We were originally going to increase it to $20M, enabling us to raise more, but we felt given the economic uncertainty as covid hit that we should take the money as fast as possible in case the US went into a recession.

It's important to note that the downside of SAFEs is that if you have a down round at the next phase of fundraising, you'll get very diluted (if the price is lower than the cap).

We've no affiliation other than being friends, but in order to model how much of the company you're selling during this process, we used Pulley. You put in all the SAFEs and you can model out a series A to check how much you've sold. Sam Altman's advice is to try to give up no more than 10-15% in a seed round and 15-25% in your A round… although "it's far more important not to run out of money than almost anything else". We used Clerky to generate the SAFEs and to send them for electronic signature.

If you have traction or a great vision, the world is what you make of it in fundraising. If you act meek and ask investors to make up the price, you'll land very low. Go in high and you'll polarize people - which is what you need… a definite yes or definite no! Just be careful if you set the bar too high, you will want to jump over it in the next round.

Getting the first cheque

We started off by speaking to some friendly angel investors. These are generally wealthy individuals who fall into two categories. Some are just plain passionate and love the idea of what you're working on. Others angel invest full time and are like a mini fund.

To find angels, we thought about who we already knew and the founders of other companies similar to ours but much bigger. As we built the company, we got advice from many people along the way. We asked them. Some invested directly, others pointed us in the right direction. People were very responsive when we asked for specific help, and we will do our best to pay that forward. When people helped us, we tried to keep them posted on how we'd followed or not followed their advice so they could see that we really did value their time.

Getting the right investors

Many investors are very hands off, others will put a lot of resource into helping you.

If you have the luxury of choosing, which happens towards the end of your round when you've already raised enough to survive, it's worth thinking about this.

More hand holding is probably better if you have less experience or you need someone to push you. We were worried that some of the more supportive investors were so supportive we'd struggle to realize that the company/project's success or failure ultimately is our responsibility - not theirs. We are the ones speaking to users every day.